A little known fact of the war in Syria is that it started at the end of the worst drought in Syrian history, a biblical drought which forced over 1 million farmers into the cities.

Pulitzer Prize-winner Thomas L. Friedman interviewed Syrian refugees and farmers in Syria about the link between this drought and the start of the civil war. He comes to the conclusion that the drought certainly played some role and was probably a key tipping point for a bad situation to turn into a full scale war. In the documentary “Years of living dangerously” we see how wiki-leaked diplomatic cables and high level US officials such as Condoleezza Rice acknowledge this link.

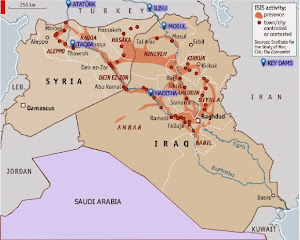

But there’s a lot more happening to explain why behind the veil of a quest for an Islamic State (IS), there’s also a war for water in Syria and Iraq. Making the plight of citizens worse is the continued targeting of water supply networks by both regime and opposition forces, which have attacked strategic lifelines, such as water channels, to gain control of territory and to punish and put pressure on their opponents.

Opening the flood gates …

The Islamic State’s quest for hydrological control began in Syria, when it captured the Tabqa Dam in 2013. Rebel-held areas had been systematically denied electricity by President Bashar al-Assad’s forces in their effort to turn the population against the insurgency. The Tabqa Dam was built more than 40 years ago with Russian help and aimed to make Syria self-sufficient in energy production. Behind the dam is Lake Assad, which provides millions of Syrians with drinking water and is a vital irrigation source for farms. After the capture of the dam, IS opened the flood-gates to get maximum electricity supply for the areas they control and win favour with the local population. As a result, the lake dropped six metres, to a record low in May, which worsened the plight of millions of already destitute Syrians as severe water cuts began to hit Aleppo province.

Conflict over the water flowing though the Euphrates and Tigris is of course nothing new and predates religious wars. They were the first rivers to be used for large scale irrigation, in the region once known as the Fertile Crescent. Somewhere between 1720 and 1684 BC, a grandson of Hammurabi dammed the Tigris to prevent the retreat of rebels led by Iluma-Ilum, who declared the independence of Babylon. The Euphrates was already used as a weapon somewhere around 2500 BC, in another fight for Babylon, when the king of Umma cut the banks of irrigation canals alongside the Euphrates dug by his neighbor, the king of Girsu.

The Euphrates and Tigris are the two major and longest rivers in the Middle East. They both originate in Turkey. The Euphrates flows through Syria and Iraq to reach the Persian Gulf while the Tigris flows through Kurdish territory, meeting up with the Euphrates in the Southern Mesopotamian Marshes of Iraq. There are currently at least 46 dams in the Tigris-Euphrates basin, with at least 8 more planned or under construction. These dams have become key pieces of geo-political control in the region.

… and shutting down the flows

While one act of war is opening the flood gates, another is closing them. In 1974, Iraq threatened to bomb the same Tabqa Dam in Syria, alleging that the dam had reduced the flow of Euphrates River water to Iraq. But between then and now, Turkey, through its position upstream, has taken over as the most powerful regional commander of water, by completing the giant Ataturk Dam. In 1990 Syria and Iraq protested that Turkey now has a weapon of war: by closing the gates they could leave them dry. They had good reason to protest. In mid-1990 Turkish president Turgut Özal threatened to restrict water flow to Syria to force it to withdraw support for Kurdish rebels operating in southern Turkey.

In April 2014, the Islamic State blamed the low water levels in Lake Assad to Turkey’s closure of the Ataturk Dam. Sources found by Al Jazeera said that these claims are disputed. But even if the allegations are only partly true: they were used by the Islamic State to issue threats to ‘liberate Istanbul’, if that was necessary. So while Turkey, IS and Assad fight over water, millions of ordinary Syrians and Iraqi’s see their water levels drop dramatically. Not just by a new drought, with rainfall down by 50-85 percent since October 2013, but mostly due to a power struggle.

Tensions over water control in the region are set to heat up further if Turkey completes the Ilisu Dam on the Tigris River near the border of Syria. The Ilisu Dam will generate 1,200 MW and is part of the vast and ambitious Southeastern Anatolia Project, known as GAP after its Turkish title (Guneydogu Anadolu Projesi): a network comprising 22 dams and 19 power plants. The Ilisu reservoir will flood 52 villages and 15 towns, including Hasankeyf, a Kurdish town of 5,500 people, which is the only town in Anatolia that has survived since the Middle Ages and is under archaeological protection. It will displace approximately 16,000 people in the troubled Kurdish region.

The World Bank (WB), the British construction company Balfour Beatty and the Italian company Impreglio have all withdrawn from the problematic project. So have international funds and export credit from Austria, Germany and Switzerland. However, the project is currently funded by Turkish banks. Iraq and also Syria will be the most heavily impacted if the dam and others go through, with the most extreme projections holding that, owing to a combination of climate change and upstream dam activity, the Tigris and Euphrates rivers won’t have sufficient flow to reach the sea by as early as 2040.

If you live in Syria or Iraq and the water irrigating your field stops coming you might join the ranks of any army promising to attack those who kept the water for themselves – no matter if they tell you the truth or not. As is often the case in conflicts or epidemics it is not the facts themselves that count most but what people believe to be the facts. Those who can convince it’s the enemies fault that there’s not enough water will have the key to where the hearts and minds of the people will go to – no matter what the facts are.

The US finally finds a Weapon of Mass Destruction in Iraq

The Tabqa Dam is not the only dam attacked by IS. They are also trying to take the Haditha Dam, the second-largest in Iraq, raising the possibility of catastrophic damage and flooding. On Sunday, the US was bombing IS positions close to the dam. The IS militants are also fighting for control of the Euphrates River Dam, about 120 miles northwest of Baghdad and government forces were fighting to halt their advance. Insurgents from IS seized the Falluja Dam in Iraq in February and closed the floodgates to cause upstream flooding and to cut downstream water supply. Some 40.000 people were displaced just to flood the area around the city of Falluja to force government troops to retreat and lift a siege, while cutting water supplies and hydroelectricity generation for other parts of the country. All that was peanuts compared to what IS did next.

On August 7 IS captured the 1GW Mosul Dam on the Tigris – sending shock waves through Bagdad, Kuwait and the US. Whoever controls the Mosul Dam, the largest in Iraq, controls most of the country’s water and power resources. Located on the Tigris River upstream of Mosul, the dam, 3.6 km long and with 320 MW of capacity daily, formerly known as the Saddam dam, was built beginning in 1980 at a cost of 1.5$ billion USD, to bolster the regime during the Iran-Iraq war by a German-Italian consortium that was led by Hochtief Aktiengesellschaft. Its construction submerged many archaeological sites in the region yet more troubling is that because the dam was constructed on a foundation of soluble gypsum, it requires continuous grouting of the dam’s foundation to promote stability. Due to the engineering problems it presents it has been described recently by US engineers as “the most dangerous dam in the world.” And that was before the “most dangerous terror group ever” captured it.

A senior U.S. administration official said that “The failure of the Mosul Dam could threaten the lives of large numbers of civilians, threaten U.S. personnel and facilities – including the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad – and prevent the Iraqi government from providing critical services to the Iraqi populace,” (Source: Reuters). A 2006 U.S. Army Corps of Engineers report obtained by the Washington Post said the dam, which blocks the Tigris and holds 12 billion cubic meters of water, could flood two cities killing over a half a million people if it were destroyed or collapsed. The tsunami going to Mosul, a city of 1.7 million people, can be 20m high if the dam breaks with a full reservoir.

But even without a catastrophic failure, the dam is already at the epicenter of the war. Soon after the Islamic State captured the Mosul Dam they cut supplies to some villages in the north of the country that have not joined their cause. Recapturing this instrument of war was a sufficient reason for US forced to deploy air power to support Kurdish forces to recapture the dam. Saving the Yazidis from their mountain captured most media attention, but a key reason for the US to bomb Iraqi soil for the first time since 2011 was the fact that IS took the Mosul Dam. After bombing IS positions for several days, freshly re-equipped Kurdish fighters recently regained control of the dam.

Mega Dams & Water Management Practices

The importance of hydro-infrastructure in these battles and how it can be wielded firstly underlines the need for a serious re-appraisal of water management practices. Big dams (with funding from Multilateral agencies such as the WB, national and regional development banks, private equity and pension funds as well as from the Clean Development Mechanism, etc.) cause large scale displacement of populations, are ecologically destructive, wash away any other source of livelihood, and often saddle countries with debt while performing well below planned outputs as regards electricity generation. Moreover, compounded by climate change, contemporary ecological crises are leading to ever more conflict over trans-boundary water rights, such as for example between Ethiopia and Egypt, which are also on the verge of war over the construction of the Grand Renaissance and Gibe 3 dams, which would become Africa’s tallest. The world’s Big Dam Fan Club should take note of what has just happened in Syria and Iraq and realise that once disaster hits, hatred will not go to any God but to those who constructed the weapon of mass destruction. Water, rather than oil, is shaping up to be the key strategic resource in the region. More